Every single person in the class raised their hands. I was especially eager to put mine up since I played her on stage when I was fourteen!

He then followed with, “How many of you have ever heard of Hannah Senesh and her diary?”

No one.

“I figured,” he said, before launching into a lecture that would impact my life unlike any other during my undergrad.

“No disrespect to Anne Frank, whose influence as a historical figure cannot be denied. But if you want a much more interesting diary that tells a much more interesting story—the story of a gutsy young woman taking a stand against the Nazis—read Hannah Senesh.”

Hannah Senesh (the commonly anglicized version of the Hungarian Szenes although you see her name appear both ways) died fighting Nazi persecution at the age of 22. She trained as a paratrooper with the Royal British Air Force to take part in one of the only known rescue missions into an occupied country at the end of World War II. The purpose was to save Jewish lives. The entire story of Hungarian Jewry during the Holocaust is fascinating, and you can watch a beautiful documentary of Hannah’s life in this context called Blessed is the Match: The Life and Death of Hannah Senesh, directed by Roberta Grossman (2008). I will offer you a very rudimentary summary here to better explain my relationship with her.

Hannah was the daughter of a famous Hungarian playwright, born at a time when the Jewish population in Hungary was very assimilated. Hannah was not really aware of what it even meant to be Jewish until the rise of Nazism in Europe and its first impact on her—being told she was no longer allow to go to the school she had been attending. To cope with these increasing experiences of anti-Semitism in her own life, Hannah made a choice to dive fully into studying Hebrew language and Jewish teaching, and she neutralized her initial shame by learning to take great pride in what it meant to be a Jew. Hannah emigrated from Hungary to Palestine in 1941 to study farming. Her mother originally protested because Hannah was a brilliant student and saw farming as a waste of her academic talents. She eventually consented, sensing the rising instability in Europe. While learning to work the land, Hannah also began writing in Hebrew, specifically in the genre of poetry. Hannah joined the Women’s Auxiliary Unit of the British Royal Air Force in 1943, training in Egypt for her ultimate mission: to parachute into Partisan Yugoslavia alongside other Jews living in Palestine with the intention of crossing into Hungary to extract as many Jews out as possible.

Hungarian Jews were largely spared during the earlier years of the World War II, yet by the end of the war the Nazi tide swiftly moved through Hannah’s own country. When she went on her mission in 1944, her ultimate motivation was to spare her mother and as many Hungarians as possible from the fate of Auschwitz. Hannah was arrested and exposed as a British spy soon after crossing into Hungary, ultimately being tortured, “tried,” and ultimately sentenced to death by firing squad in a Gestapo prison. In an interesting footnote that is better explained in the documentary, Hannah’s stand ultimately saved her mother’s life. Instead of being sent to a death camp, Hannah’s mother was imprisoned alongside of her on suspicions that she was a co-conspirator. The trial of Catherine Senesh, Hannah’s mother, kept getting delayed and the war eventually ended before she could be tried.

After Dr. Friedman told me about her, I read her diary, her poetry translated into English, and everything written about her—I felt that the bravest young woman of my age I had ever met came alive for me! I was not raised Jewish although studying Anne Frank at an earlier age and studying Hannah in college began my interest in learning more about Judaism. I wondered why history had not granted Hannah the same reverence as Anne Frank? Was it because Hannah was considered a Zionist and is still largely heralded as a hero in the Zionist movement? In the open blood sore of trauma and traumatic reenactment that defines life in much of the Middle East, Zionism can be a dirty word.

Although Dr. Friedman entertained this conjecture, his ultimate contention rings prominently for me to this day, “History usually loves the good girl who believed that deep down people are really good at heart. Anne is safe. Hannah was a rebel.”

When he put it that way, I found what in EMDR therapy or other trauma-focused therapy terms we may call a protector figure. Historical figures can be used as such protector figures, and we can sense their presence, their support, and use their example to guide us into our deeper work. Hannah was my first historical protector figure before I even knew the jargon of that therapy term I now use so readily in my teaching! Her most famous poem, Blessed is the Match, which she gave to one of her squadron members just before she crossed into Hungary, became a guiding prayer through those rough undergraduate years when I was struggling to claim my own identity.

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame

Blessed is the flame that burns in the secret fastness of the heart

Blessed is the heart with strength to stop its beating for honor’s sake

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame

If you want to know why I resonate with Hannah’s story and life so much, take in this poem. I made a poster of Blessed is the Match and hung it up in my dorm room. As I struggled to learn how my heart really worked around issues like my faith, my sexuality, and the clash between my learned self-hatred and an innate belief that who I authentically am could bring about some good in the world, Hannah’s poem sustained me. In the throes of my most active addiction that lasted from age 19-23 (the ages where Hannah had set off to redefine herself and change the world in her own way), I believe that reciting Blessed is the Match kept me alive quite a few times. My heart never stopped beating, even though I wanted it to many times in that era, because as it turns out, my Higher Powers and the world were not yet done with me.

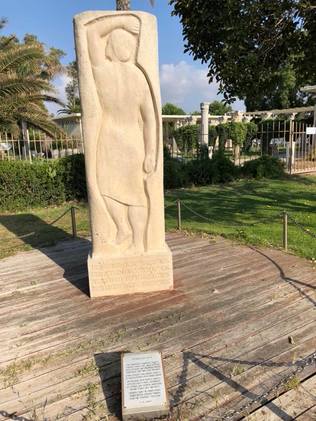

I write this tribute, this letter of love and thanks to Hannah, on my first journey to Israel. I had the chance to visit Hannah’s monument at Sodt Yam, the kibbutz near Caesarea where she worked before joining the British Royal Airforce. Blessed is the Match appears in Hebrew on the base of her statue. After a day of moving through clogged traffic, the tension evident to me in Jerusalem, and other sites packed with noisy Western tourists, I sat on the kibbutz in Sodt Yam the only visitor. I admired her monument, which struck me as a classic embodiment of a Divine Feminine, the sun of the Mediterranean setting against my back. Although I appreciated the quiet and quickly realized why she loved this place so much (honored in her poem Eli, Eli that was eventually set to music), my solitude as the only Westerner around made me rethink Dr. Friedman’s question: How many of you have ever heard of Hannah Senesh? It’s a question I’d like to yell out at the top of my lungs to everyone at the tourist sites and if the answer is no, why haven’t you?

This tribute is my small way of sharing a major influence, a protector figure, with people who are likely to read my work. I know it’s a risky piece to write as I fear that it may be quickly politicized because of who Hannah was. As much as I’d like to say, keep politics out of it, I know that may be impossible for many, regardless of where we stand or how we feel about the cause of tensions in the Middle East. Whenever issues of identity are at stake, it’s difficult not to feel issues personally or become enraged by injustices. I would like to think that Hannah’s heart is breaking to see what is happening in this part of the world, her homeland that she loved so much. So, I end my tale by telling you specifically why I thanked Hannah at her beloved Sodt Yam—because she never once left me or the nineteen-year-old self who still lives within me. The match she lit for me all those years ago recently helped me to be brave, strap on my parachute and fly.

I’ve not publicly announced this yet in any of my writing and will keep the details limited since healing is still a work in progress. The last three years were particularly turbulent for me in realizing that I had to live my life as fully and as authentically as possible to be my healthiest self—and I wasn’t doing that. The deaths of several people close to me made me realize just how much of myself I was hiding, both with my professional voice and issues around personal identity. The shameful remnants of the religions in which I was raised clashed up against my sexual identity. My renewed drive to be an unapologetically feminist voice in a country where disrespect towards strong women still abounds toppled many of the internal messages I still carried about the importance of being a nice girl. And I came to a place where enough was enough. I was playing it safe, not speaking up nearly enough about issues that mattered to me, for the sake of being too diplomatic. In a country where strong females are still regularly mocked with pejoratives and insults, my fear of not being liked or making too many waves kept me silent on issues in every area of my life . This surprises many people who have long seen me as outspoken. This meant I had to make the difficult decision to leave my second marriage, wading through the negative self-talk around, “Oh what will people say? She helps so many other people and can’t keep her own shit together.”

Hannah helped me torch this script. Literally.

One night during a therapy retreat with my personal EMDR therapist, I was also reading work on the four elements by Christine Valters Paintner, one of my spiritual teachers. In doing a meditation on fire, I felt Hannah’s presence so strongly and Blessed is the Match, a poem I hadn’t consciously prayed in years, ignited my heart. I had not yet left my marriage but was getting close, and using my trauma healing knowledge to strengthen the resources that Hannah gave me all those years ago helped me to leap with both the fear and excitement she may have felt jumping out of that plane. When I sensed into that resource, I literally felt like she was giving me her parachute.

Hannah’s parachute represented and continues to represent Spirit/Source or my Higher Power, the assurance that even in the face of risk and maybe even eventual fallout, there’s a larger purpose in everything and I am loved. Her match represents validation that my heart and all its complexities are sacred just as they are, and can play some small role in bringing warmth and light to a world that is cold and dark. Being myself this fully is a risk, and it’s one that is worth taking!

Through all the difficult days and battles that were ahead of me in the year that followed, I carried an unlit match with me for grounding. A tangible reminder of her gifts and her role as a protector figure. She is one of many forces, in this realm and in the realm of spirit, who has my back, and for their light and their lineage, I am immensely grateful.