Changing Lives Through Lived Experience

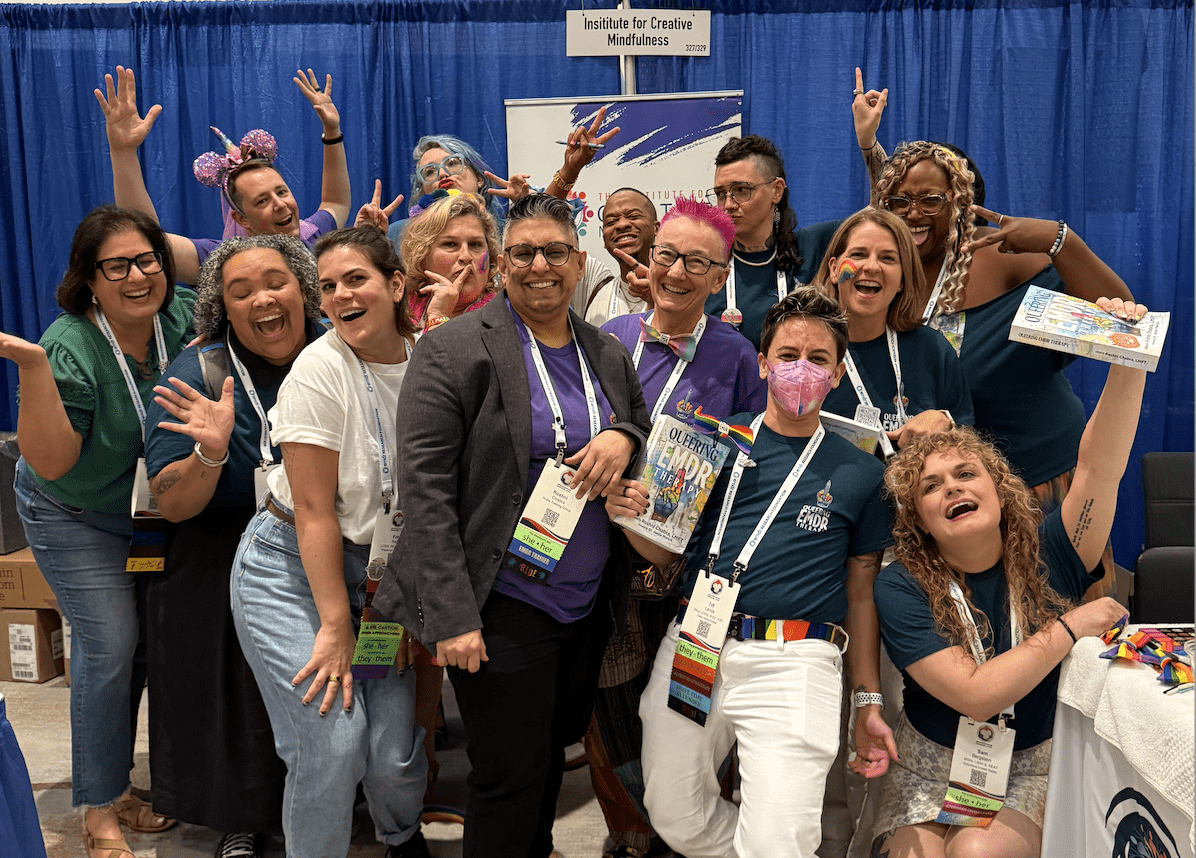

Tears filled my eyes when I took to the podium for my presentation at the EMDR International Association (EMDRIA) Annual Conference on Sunday, September 14

Tears filled my eyes when I took to the podium for my presentation at the EMDR International Association (EMDRIA) Annual Conference on Sunday, September 14

When I was in sixth grade, my cousin and I went to a Lady Gaga concert in Detroit. It was, in many ways, a queer

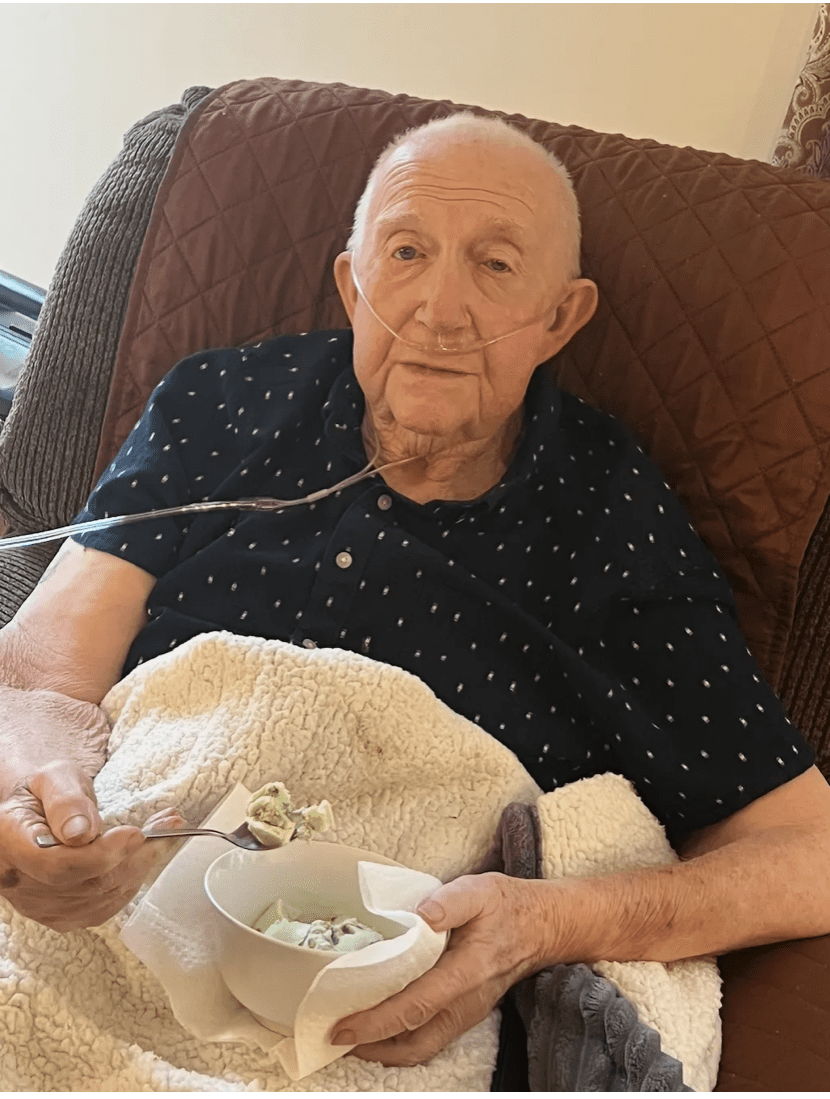

During the last six weeks of his life on this earth, I brought my Baba all the ice cream that he wanted. One night in

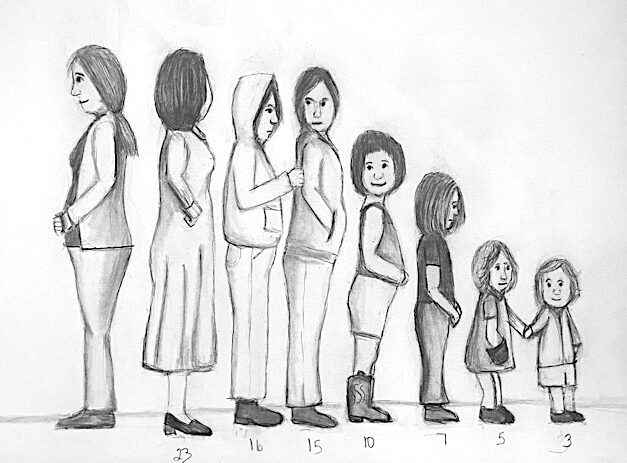

I couldn’t scream. Yet, there were those inside that wished they did. A little girl who wanted to scream But instead was still. Frozen with

(CONTENT WARNING: This contains personal recollections of childhood sexual abuse, fat shaming, and eating disorders.) A few years ago, I decided it was time for

Hey you. Yes you. I see you. It’s ok if you’re not ready to talk. I hope it’s ok for me to share a few

I’ve written several pieces inspired by my friend Jason Fair on this blog. You can check out Merry Christmas, Jason, published just two weeks after

When we are called imaginary, we reappear. When we are called real, we disappear. When no one arrives, we appear. When no one calls, a

This poem is inspired by a road sign we saw whilst on the Australia part of our pilgrimage: “Don’t trust your tired self.” Inspired by