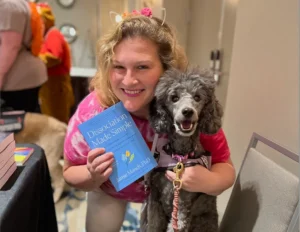

So it’s no wonder, like any obsessed sports fan, that I spent the better part of fifteen years after leaving high school involved in high school speech in some manner as a coach. And coaching young people on several different types of teams proved even more transformational than my own high school speech experience. Yes, I was a “speechie” in high school, as we are often called, yet being a coach crystalized the power of that identity in my being. For this reason, I dedicated my newest book Process Not Perfection: Expressive Arts Solutions for Trauma Recovery to my students, the “speechies” that I coached between 1997 (the year I graduated from high school) until 2011. As I reference in the dedication, they truly taught me the power of expressive arts as healing.

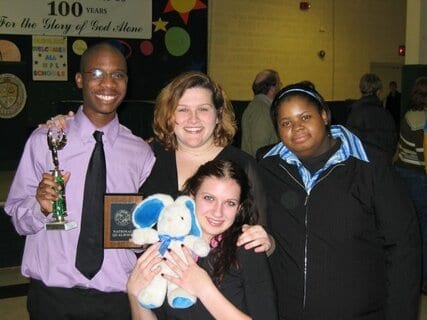

I coached on four teams during that time—I assisted at two schools while I was an undergraduate. I had the privilege of being the head coach of Chaney High School, my alma mater, when I was in graduate school and during the first two years of clinical career. To coach a Chaney kid to a state title, and coach another to three state final rounds in three different categories during his tenure, brought my “small team” kid experience full circle. I thought I was done…what could top that? Then in 2008, when I moved to one of those suburbs I once growled at when I was a city school kid in Youngstown, OH, the head coach of that team (an old friend of mine), pulled me in for one more go as his assistant. I got to coach on two state championship teams, a new experience for me having always either been on a small team or having coached one.

During all of these stints I met such awesome young people—I can think of no other adjective for their spirits or for the experiences I had coaching them. Coaching is not quite the best word. Rather, I had the privilege of guiding them through process, the construct I now celebrate in my work as a trauma-focused expressive arts therapist. To be in process as you prepare for competitive speech, especially if you want to see good results, is to be constantly willing to engage in trial and error. As a coach I often guided my kids through one sentence of their speech or performance piece in thirty different ways, just to test it out and notice what best popped. This same idea applies whether a student is in more of a performance-based category like drama, humor, or poetry reading, or one of the classic speaking categories like original oratory.

Working with my students is where I really developed the competency of listening with my body, a skill that has served me well as a trauma-focused therapist and expressive artist. You listen and you notice with something that often can’t be put into words for a sense of “That’s it!” These moments can happen at 7:00pm at night in a high school classroom, long after other students have cleared out. And then your student may take it to a tournament, try it out, and it falls flat, which can be an invitation back into process. Or, they may take the fruits of their work to a tournament and, following the flow of their intuition, may create even more magic than you or they even thought possible during those hours of practice.

I wish that I could tell stories about all of my students in this piece, but there is simply not enough room! A book wouldn’t even suffice. In reality, they all taught me something. Even the kids who resisted the depth of practice it would take to be competitively successful taught me about process, whether that was getting to explore resistance or to realize that for some kids it’s never about winning. The process is in the having fun, enjoying friendships and trying something new in their high school speech experience. In expressive arts therapy we talk a great deal about the work not being outcome-focused. Because competitive speech is, well, competitive, the end result was imperative to many of the students I coached. It was to me at the end of my high school speech career which is why I don’t think I enjoyed it as much as I could have. Yet I inevitably found that the students who were willing to dive in and embrace the process—the trial and error, explore the range depth—ended up being most successful in terms of trophies and titles won. I think there is a lesson here for those of us who pursue the arts professionally in one way or another—the power is in the process. Focus on the process, and you may be utterly amazed at the outcomes you are able to achieve.

And then we can pick apart what it even means to be successful. In reflecting back on my own high school speech career, I never came close to achieving the success that many of my students did. Yet I now have a professional career and public image that is based largely on my ability to speak publicly. I remember the first time I offered a continuing education training for other professionals in 2007, one of my colleagues asked, “Where did you learn to hold a crowd like that?” I chuckled and replied, “You have no idea,” thinking fondly on all of those hours I spent preparing with my own coaches and friends in high school, talking to walls (a common warm up practice on tournament day), and then working with my own students. The trophies have been thrown away or recycled and yet the fruits of the process remain.

Now looking back, the students who had the most impact on me are those who were never major contenders for awards. Yet I saw them blossom in terms of confidence and ability to stand tall and speak their voice. I remember one student who came to me during my second stint as an assistant, asking me if he could still be on the speech team even though he had a speech impediment. I adored his spirit right away and welcomed him aboard. He is now a lawyer. The person I coached to the state title at Chaney is a teacher and speech coach herself in Baltimore, and I beam with the pride of a mother when I see the pictures she posts at tournaments with her own students.

So many of my former students are making a real difference in this world, regardless of their chosen profession. Through the wonder of social media and texting, I am still in touch with many of the young people I had the joy of coaching through the years. Instead of talking about gesture placement and intonation, we now talk about life. It warms my heart that they can still seek out my experience, strength and hope… and it’s a two-way street. When I hear some of the young people, I coach make such intelligent life connections that I wish I would have made at 22 or 23, I smile and thank them for sharing a lesson with me.

And this is what I mean by all life being a chance to engage in process.